Over the last 90 years or so, the United States has transformed into the very thing the founding generation fought to destroy.

We learn in elementary history classes that American revolutionaries rejected the notion of a king. But it went beyond that. The founding generation also sought to eradicate the concept of a powerful magistrate who ruled over the people and was empowered to make law. As the Americans split with Great Britain and forged ahead forming new governments, they were ever-fearful of vesting power in individuals detached and unaccountable from the will of the people.

The British colonial governors ruled with that kind of authority. The founding generation would have no more of that. As the people of the states began to draft their own constitutions, they placed very little power in the executive branches.

In his book Creation of the American Republic, historian Gordon S. Wood put it this way.

The Americans, in short, made of the gubernatorial magistrate a new kind of creature, a very pale reflection indeed of his regal ancestor. The change in the governor’s position meant the effectual elimination of the magistracy’s major responsibility for ruling the society – a remarkable and abrupt departure from the English constitutional tradition.”

This represented a clean break from the then-accepted philosophy of government. In the Old World, executives wielded tremendous power. Americans instead vested their legislatures with the greatest level of authority.

Why?

Americans feared the arbitrary power they so often saw exercised by magistrates in the past. And as Wood put it, “only a radical destruction of that kind of magisterial authority could prevent the resurgence of arbitrary power in their land.”

The founding generation believed legislatures best reflected the will of the people because they were directly accountable. And the founding generation believed sovereignty was ultimately vested in the people, not in any government institution.

Governors in the new state governments were thus relegated to merely “executing the laws,” essentially an administerial role.

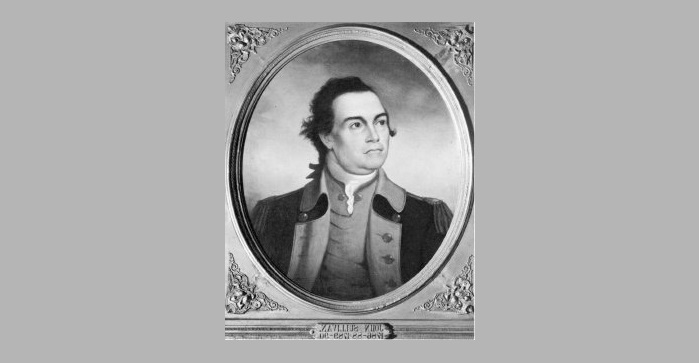

John Sullivan served as a general in the American Revolution, and later as governor of New Hampshire and a federal judge. He took a break from fighting in the winter of 1775 to pen a letter to Meshech Weare outlining his thoughts on forming a new state government He warned against vesting too much power in a single person.

And here I must beg leave to observe that, however high other people’ s notions of government may run, and however much they may be disposed to worship a creature of their own creation, I can by no means consent to lodging too much power in the hands of one person, or suffering an interest in government to exist separate from that of the people, or any man to hold an office, for the execution of which he is not in some way or other answerable to that people to whom he owes his political existence.”

Today, we have utterly abandoned the principles articulated by Sullivan that America was founded on and returned to the system of unaccountable, absolute rulers the founding generation fought to free itself from.

Of course we don’t have kings. We don’t have all-powerful governors. In modern America, federal judges fill the role.

The United States’ political system has devolved into government by judiciary.

It started almost immediately after the ratification of the Constitution, but took off in earnest after the Supreme Court began redefining the meaning of the 14th Amendment in 1925. Federal judges legislate from the bench. They rewrite state laws. They impose edicts on local jurisdictions. They substitute constitutional fidelity with their own political agendas, ruling in a manner they think “best for America.”

Like the King of England and his colonial governors, modern federal judges operate with no direct accountability to the people. They represent everything that Gen. Sullivan warned about. They, in fact, are not answerable to that people to whom they owes their political existence.

Thomas Jefferson saw it coming way back in 1823.

At the establishment of our Constitutions, the judiciary bodies were supposed to be the most helpless and harmless members of the government. Experience, however, soon showed in what way they were to become the most dangerous; that the insufficiency of the means provided for their removal gave them a freehold and irresponsibility in office; that their decisions, seeming to concern individual suitors only, pass silent and unheeded by the public at large; that these decisions nevertheless become law by precedent, sapping by little and little the foundations of the Constitution and working its change by construction before any one has perceived that that invisible and helpless worm has been busily employed in consuming its substance. In truth, man is not made to be trusted for life if secured against all liability to account.”

Americans would do well to abandon their fixation on federal courts. They were never intended to wield the level of power they hold over us today, and they hide in their underbelly the seed of tyranny.

“It is not enough that honest men are appointed judges. All know the influence of interest on the mind of man, and how unconsciously his judgment is warped by that influence. To this bias add that of the esprit de corps, of their peculiar maxim and creed that ‘it is the office of a good judge to enlarge his jurisdiction,’ and the absence of responsibility, and how can we expect impartial decision between the General government, of which they are themselves so eminent a part, and an individual state from which they have nothing to hope or fear?” –Thomas Jefferson: Autobiography, 1821. ME 1:121