Freedom of speech and freedom of the press were among the core liberties many American believed needed express protection in a bill of rights from infringement by the newly created federal government.

Freedom of speech and the press find their roots in the same soil – liberty of conscience. If people have the right to think and believe as they see fit, it logically follows that they should also have the right to express their ideas freely.

Freedom of speech and the press also serve an important political function. The founding generation considered them “the palladium of liberty,” meaning they provide vital protection or a safeguard.

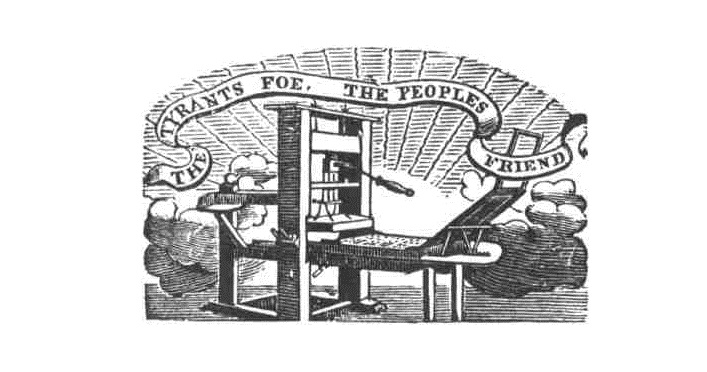

During the Virginia ratifying convention, delegate John Dawson called liberty of the press “sacred” and said the influence of the press “is so great that it is the opinion of the ablest writers that no country can remain long in slavery where it is unrestrained.” South Carolina ratifier James Lincoln called liberty of the press “the tyrant’s scourge.”

Many in the founding era feared federal regulation of the press would eventually lead to tyranny. Writing in the Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal in October 1787, the penmen Centinel emphasized the importance of maintaining a free press to a free society.

As long as liberty of the press continues unviolated, and the people have the right of expressing and publishing their sentiments upon every public measure, it is next to impossible to enslave a free nation…Men of an aspiring and tyrannical disposition, sensible of this truth, have ever been inimical to the press, and have considered the shackling of it, as the first step towards the accomplishment of their hateful domination, and the entire suppression of all liberty of public discussion, as necessary to its support.

Thomas Jefferson made a similar point in a 1787 letter to Edward Carrington.

The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

But freedom of expression wasn’t only considered a matter of political concern. An Old Whig wrote in 1787, “Should the freedom of the press be restrained on the subject of politics, there is no doubt it will soon after be restrained on all other subjects, religious as well as civil.”

Notice that the right of expression wasn’t reserved for some professional, privileged class known as the press, or just for “journalists.” Freedom of speech and the press stands as a right of the people – all of us.

Proponents of the Constitution insisted the federal government could not regulate the press or infringe on free speech because the founding document delegated no such power to it. South Carolina’s Charles Cotesworth Pinckney made this argument.

The general government has no powers but what are expressly granted to it; it therefore has no power to take away the liberty of the press.

But those insisting on a Bill of Rights as a condition of ratification rightly pointed out that even legitimately delegated powers opened the door for restraining the press or speech. For instance, the government could use the power to tax to strangle the press, as the Federal Framer argued in January 1788.

All parties apparently agree, that the freedom of the press is a fundamental right, and ought not be restrained by any taxes, duties or in any manner whatever. Why should not the people, in adopting a federal constitution, declare this, even if there are only doubts about it? But say the advocates, all powers not given are reserved; – true; but the great question is, are not powers given, in the exercise of which this right might be destroyed.

Those arguments ultimately won the day, and prohibitions on abridging the freedom of speech and the press were included in the amendments proposed by James Madison on June 8, 1789.

Fourthly, that in the 1st, section 9, between clauses 3 and 4 [of the Constitution] be inserted these clauses to wit…The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks or liberty, shall be inviolable.

These ideas were ultimately included, along with freedom of religion, petition and assembly in what we now know as the first amendment.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Next we will look at the First Amendment religion clause.