So far in the Constitution 101 series, we’ve established that the Constitution created a limited federal government meant to exercise only specific, enumerated powers. All other authority remains with the states and the people. We also discussed the fact that the people stand as the sovereign in the system, and the Constitution was ratified by the people, through preexisting political societies – the states.

This construction of the federal government was implicit in the original Constitution. The Tenth Amendment made it explicit.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Understanding these concepts raises an important question: what keeps the federal government limited to its enumerated powers?

Words on parchment mean nothing without some mechanism to enforce them, and the founders intended the states to serve as that necessary check on federal power.

Before the Constitution was even ratified, James Madison laid out a blueprint for addressing federal overreach in Federalist 46. The “Father of the Constitution” said that if the federal government imposes “unwarrantable measures” (or even warrantable measures) the “means of opposition is powerful and at hand.” He mentioned a number of steps states could take including “refusal to cooperate with officers of the union” and other “legislative devices, which would often be added on such occasions.” Madison said that even a single state implementing these measures would impose “very serious impediments,” and when several states take action together, he said it would “present obstructions which the federal government would hardly be willing to encounter.”

Federalist 46 laid the foundation for nullification.

Broadly speaking, nullification includes any act or set of acts that serve to render a federal action null, void or simply unenforceable within the borders of a state.

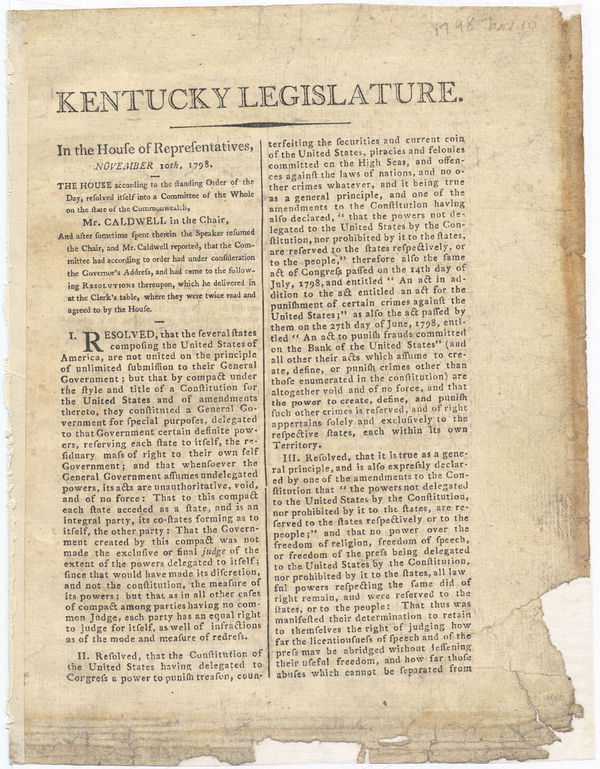

Madison and Thomas Jefferson first formalized the principles of nullification in the Kentucky and Virgina Resolutions of 1798 in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. These four laws granted judicial powers to the president and limited due process for resident aliens deemed “enemies,” and outlawed criticism of the federal government, a clear violation of the First Amendment.

In the original draft of the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson rested his case for nullification on the Tenth Amendment, calling federal assumption of undelgated power “unauthoritative, void, and of no force.” He declared nullification the “rightful remedy” to deal with federal violations of the Constitution.

Where powers are assumed which have not been delegated, a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy: that every State has a natural right in cases not within the compact, (casus non fœderis) to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits that without this right, they would be under the dominion, absolute and unlimited, of whosoever might exercise this right of judgment for them.

The Virginia legislature passed similar resolutions drafted by Madison a month later.

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact; as no further valid that they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

Some call nullification illegitimate, arguing the Constitution makes no provision for it. But notice that Jefferson called it a “natural right.” Nullification rests upon a constitutional foundation and logically flows from the constitutional system, but it is not “constitutional” per se. It exists as a right reserved to the states and the people as a process to protect them from federal overreach and hold the government they created in check.

For a deeper discussion of nullification, check out my book, Our Last Hope: Rediscovering the Lost Path to Liberty. It lays out the historical, constitutional and moral case for nullification.

Next week we will consider federal supremacy.