For many Americans, knowledge of the Constitution begins and ends with the preamble. A lot of you probably even memorized it at some point in school. I suppose you could laud the educational system for at least acknowledging the existence of America’s governing document. But unfortunately, all of the focus on the preamble has done more harm than good.

For all of its poetic beauty and the sweeping principles it highlights, the Constitution’s preamble tells us very little about the American system of government as conceived by the founding generation. In fact, apart from establishing who has the ultimate authority in the system, and generally outlining the purposes of the union, it doesn’t really tell us anything. In particular, it reveals nothing about the powers vested in the federal government.

WHAT THE PREAMBLE TELLS US

While the preamble does not tell us anything about the extent of government power, it does reveal to us where that power comes from.

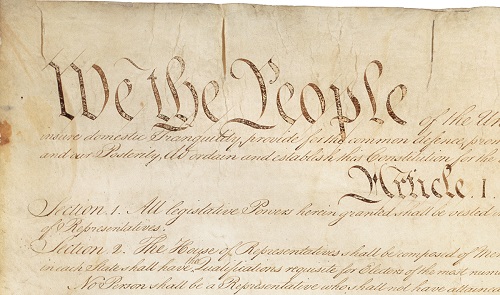

Have you ever stopped to think about why the opening words of the U.S. Constitution – We the People – appear in large, ornate letters? It’s actually significant. When an 18th century British king issued a grant, his name always appeared at the top in the same fashion. The framers of the Constitution merely replaced the king’s name with “We the People,” signifying the sovereign authority from which the delegation of power flowed. In other words, all authority in the United States ultimately flows from the people, not the government.

In the British system, the “King in Parliament” was sovereign. In practice, Parliament exercised ultimate authority with the king serving as the arm to put its power into action.The British developed a constitutional system, but not in the same sense Americans think of it today. Their constitution was not written. In the British system, no distinction existed between “the constitution, or frame of government” and “the system of laws.” They were one and the same. Every act of Parliament was, in essence, part of the constitution. It was an absurdity to argue an act of Parliament was “unconstitutional.” Since it was sovereign, anything Parliament did was, by definition, constitutional.

In the years leading up to the War for Independence, Americans began to question this theory of political power. Instead, they began to view a constitution as something existing above the government. The colonists ultimately rejected the idea that governments form the constitution and instead conceived of the constitution as something that binds government. The written U.S. Constitution established by “we the people” reflects this shift.

But “we the people” does not mean the “whole people,” or every person in America taken together as a giant glob. It would be more accurate to say “we the people of the states.” In fact, as originally drafted, the preamble listed every state. “We the people of Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia…etc.” So why did the committee of style change the wording to simply “we the people?” Because there was no guarantee every state would ratify. Say Rhode Island decided not to join the union. It would have made no sense to have it listed if it didn’t ratify. The change in style was for that purpose, not a reflection of a change in how the framers viewed sovereignty.

With the ratification of the Constitution, the states remained the preeminent political societies in the American system. As stated in the preamble, the primary purpose of the Constitution was to create “a more perfect union.” This implies the document did not create a new union, but merely built upon the existing union established by the Articles of Confederation. America’s original constitution explicitly affirmed the independence and sovereignty of the states. This basic structure carried over into the new constitution.

James Madison explained this concept in his Report of 1800 in defense of the Virginia Resolutions of 1798. In the resolutions, Madison asserted “that the states are parties to the Constitution or compact.” By this, he meant the people of the states created the union.He further developed this idea in the Report of 1800.

It is indeed true, that the term “states,” is sometimes used in a vague sense, and sometimes in different senses, according to the subject to which it is applied. Thus, it sometimes means the separate sections of territory occupied by the political societies within each; sometimes the particular governments, established by those societies; sometimes those societies as organized into those particular governments; and, lastly, it means the people composing those political societies, in their highest sovereign capacity. Although it might be wished that the perfection of language admitted less diversity in the signification of the same words, yet little inconveniency is produced by it, where the true sense can be collected with certainty from the different applications. In the present instance, whatever different constructions of the term “states,” in the resolution, may have been entertained, all will at least concur in that last mentioned; because, in that sense, the Constitution was submitted to the “states,” in that sense the “states” ratified it; and, in that sense of the term “states,” they are consequently parties to the compact, from which the powers of the federal government result. [Emphasis added]

In short, the people, organized into political societies known as states, are sovereign in the American system.

Along with revealing the ultimate source of authority in the United States, the preamble also establishes the general purposes of the union and the objectives of the general government created by the Constitution.

In a nutshell, the reasons spelled out in the preamble answer this question: why did the American states form a union?

The answer: to establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.

WHAT IT DOESN’T TELL US

While the preamble outlines the broad objectives of the federal government, it does not confer any authority to it at all. Delegation of powers follow in the various articles. Article 1 Sec. 8 delegates specific enumerated powers to Congress. Article II delegates specific powers to the president. Article III establishes the authority of the judiciary. Without the delegation of powers that follow, the preamble is nothing but a poetic list of objectives with no mechanism to carry them into effect.

Many Americans don’t understand this. They believe the preamble empowers the federal government to take virtually any action necessary to achieve the Constitution’s stated objectives. As a result, they point to it to justify all kinds of unconstitutional federal actions.They believe that the federal government can do anything and everything to “provide for the common defense,” or to “promote the general welfare,” or to “secure the blessings of liberty.”

Americans began abusing the words of the preamble almost before the ink was dry. Early on, power-seekers attempting to expand the scope of federal authority argued that the preamble authorized their actions. In fact, defenders of the Alien and Sedition Acts resorted to this tactic. Madison dispensed with their arguments in the Report of 1800.

“They will waste but little time on the attempt to cover the act by the preamble to the constitution; it being contrary to every acknowledged rule of construction, to set up this part of an instrument, in opposition to the plain meaning, expressed in the body of the instrument. A preamble usually contains the general motives or reasons, for the particular regulations or measures which follow it; and is always understood to be explained and limited by them. In the present instance, a contrary interpretation would have the inadmissable effect, of rendering nugatory or improper, every part of the constitution which succeeds the preamble.”

The preamble is like the introduction to a book. It gives you a general idea as to what the book is about. But you would never write a book report just by reading the introduction – that is if you care about getting a decent grade.

Anybody trying to justify this or that federal action through the words of the preamble is almost certainly expanding government power beyond its constitutional bounds. The preamble tells us a little, but it doesn’t reveal a lot. Americans need to keep those well-known words in their proper context.