Many Americans believe the Bill of Rights apply to state and local governments. Most who hold this position rely on the 14th Amendment and the “incorporation doctrine” to support their position. But some proponents of using federal power to restrict state and local actions through the Bill of Rights use tortured legal reasoning to argue the Bill of Rights were always intended to apply to the states, specifically the Second Amendment.

One such exercise in legal gymnastics leans on the Supremacy Clause to apply the Bill of Rights to the states. Here’s an example of this reasoning.

As I understand the Supremacy Clause, it appears that the state governments are also prohibited from ‘infringing’ on our individual right to ‘keep and bear Arms.’ The Supremacy Claus States that, ‘This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States, which shall be made in Pursuance thereof … Shall be the Supreme Law of the Land; … Laws of any State to the Contrary, notwithstanding.’

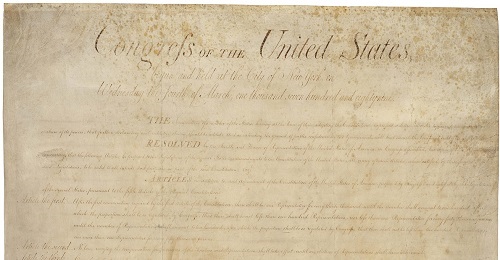

“All amendments to the Constitution, once ratified, became ‘part of’ the US Constitution, and therefor are the ‘supreme Law of the Land.'”

This assertion seems plausible on the surface. But the error in this logic lies in using the Supremacy Clause to reinterpret the Bill of Rights instead of simply applying the original meaning and intent of the amendments as the “supreme law of the land.”

As part of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights clearly stands as the supreme law of the land. But this fact tells us nothing about what the specific amendments mean, or how they apply. It only tells us that whatever they mean, and however they apply, they are the supreme law of the land.

It is clear from the preamble to the Bill of Rights, the drafting process and debates in Congress, and from the ratification debates in the states, that the Bill of Rights was intended to serve as a restriction on federal power only – not state power. Zero evidence exists that anybody in the founding era thought the Bill of Rights would apply to the states. In fact, when Madison introduced the Amendments that would eventually become the Bill of Rights, he proposed that some restrictions should apply to state governments. Those proposals were rejected during the drafting process in Congress.

Clearly the original intent was that the Bill of Rights would serve as restrictions on federal power only.

Therefore, per the Second Amendment, the federal government cannot infringe on the right to keep and bear arms. As drafted and ratified, this amendment was understood to place no restrictions on the states. This stands as the supreme law of the land. An application of the amendment to the states cannot be the supreme law of the land because that was never intended. No legal rule of construction exists that allows you to go back after the fact and reinterpret the words of the Bill of Rights in light of the supremacy clause in order to change its meaning into something that was never intended.

This fallacious reading of the supremacy clause and the Bill of Rights roots itself in a deeper misunderstanding. Most Americans think the United States operate under a nationalist political system with the states subservient to the central authority. In fact, the states remain independent and sovereign. The general government possesses limited authority subject to powers delegated to it by the states. In fact, the states and the central authority generally operate in totally separate spheres. The Bill of Rights was ratified to clarify the limits on federal authority and has nothing to do with state governments. They operate under state constitutions with their own restrictions.

Although Chief Justice John Marshall was an unapologetic advocate for national power, he explained how constitutions apply in different spheres, and the limits of the Bill of Rights beautifully in his opinion in Barron v. Baltimore.

The constitution was ordained and established by the people of the United States for themselves, for their own government, and not for the government of the individual states. Each state established a constitution for itself, and in that constitution, provided such limitations and restrictions on the powers of its particular government, as its judgment dictated. The people of the United States framed such a government for the United States as they supposed best adapted to their situation and best calculated to promote their interests. The powers they conferred on this government were to be exercised by itself; and the limitations on power, if expressed in general terms, are naturally, and, we think, necessarily, applicable to the government created by the instrument. They are limitations of power granted in the instrument itself; not of distinct governments, framed by different persons and for different purposes.

“If these propositions be correct, the fifth amendment must be understood as restraining the power of the general government, not as applicable to the states. In their several constitutions, they have imposed such restrictions on their respective governments, as their own wisdom suggested; such as they deemed most proper for themselves. It is a subject on which they judge exclusively, and with which others interfere no further than they are supposed to have a common interest.”