Today, I received an email from a “constitutional law professor” chastising me for an argument I made in the most recent installment of my continuing series on The Federalist Papers at the Tenth Amendment Center.

It was clear from the outset of the email that this professor either had not read past the article’s headline, or he suffers from some type of severe reading comprehension problem. The email is indicative of the condescension and lack of critical thinking we deal with from so-called experts all the time.

Following is his email, and my response.

Mr. Mike Maharrey,

I wanted to email you today after coming across some of your writing on the 10th Amendment Center webpage regarding Hamilton’s Federalist 16. As a Constitutional scholar I have read extensively through the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. Your interpretation really jumped out at me since it missed a very key point in Hamilton’s No. 16. Hamilton was not writing about nullification. He was making a point to show how the Confederation, that predates the current Constitution, failed to function. If you recall the title of No. 16 is, “Inability of the Confederation to Enforce Its Laws” you can plainly see that Hamilton was speaking to the failings of the government prior to our current Constitution. It is completely and utterly inapplicable to our modern system.

Quite ironically to your organization, Hamilton was speaking to the failing because under the Articles of Confederation states could nullify federally made law. The point of No. 16 is literally the opposite of your movement’s agenda.

Regardless of other parts of the Constitution you may want to review Article 6 Supremacy Clause and relevant jurisprudence relating to federal law being the ‘supreme law of the land.’

Professor,

I can only conclude from your email that you never read past the headline of my article. I never asserted that Hamilton was “writing about nullification.” My point was that he “unwittingly” revealed a truth that validates the nullification strategy of state non-cooperation. Here is what I actually wrote.

Hamilton then cites objections to state legislatures playing a role in bringing federal measures into effect, In so-doing, he unwittingly lays the foundation of state nullification.

‘If the interposition of the State legislatures be necessary to give effect to a measure of the Union, they have only NOT TO ACT, or to ACT EVASIVELY, and the measure is defeated.’

Hamilton got what he wanted in one sense. State legislatures have no say in approving or disapproving federal measures. The federal government acts directly on the American people. But states still play a significant role in enforcing the federal government’s will.

While state legislatures do not approve federal measures directly, the federal government almost always depends on state resources and personnel to carry them into effect. By refusing to act, states have the power to defeat federal measures for all practical purposes.

In fact, state interposition is necessary to enforce federal will today because the federal government depends on state cooperation to implement and enforce virtually all of its acts, regulations, programs and laws. Therefore, states can nullify them in effect by withdrawing that vital support.

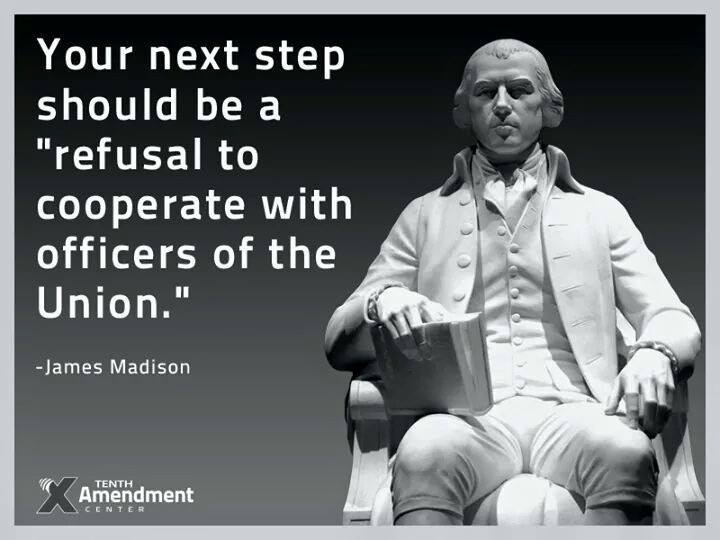

So, I never said that Hamilton was somehow advocating nullification. I said that his observations regarding states in Federalist #16 reveal the federal government’s weakness and validates this particular nullification strategy. In fact, Madison advocated exactly this kind of non-cooperation in Federalist #46 as a way to check federal power.

I appreciate your recommendation to review the “supremacy clause.” But in fact, I am quite familiar with it, including the all-important words “in pursuance thereof.” I understand why a lot of people miss those. Constitutional scholars tend to replace them with an ellipsis when writing for the general public. As a result, a lot of people operate under the misguided notion that the federal government can do whatever it wants because – “supremacy.” In fact, federal supremacy was meant to be limited to constitutionally delegated powers.

You may want to review Jefferson’s original draft of the Kentucky Resolutions and Madison’s Virginia Resolutions of 1798. I will extend to you the same challenge I have offered to numerous constitutional law professors – refute their logic and understanding of the structure of the federal government and the authority of the states using ratification era sources.

Have a lovely weekend,

In liberty,

Mike Maharrey