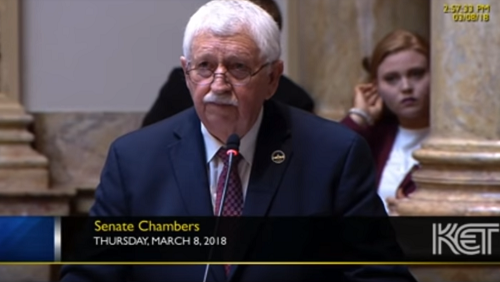

Kentucky state Sen. Albert Robinson (R-London) has been a vocal opponent of legalizing medical marijuana in the commonwealth. He has based his opposition on the Constitution’s “supremacy clause” arguing that Kentucky cannot pass a law that contradicts federal statute. Unfortunately, Sen. Robinson demonstrates a gross misunderstanding of what federal supremacy actually means. He also ignores a well-established legal precedent that makes the argument about federal supremacy superfluous in the medical marijuana debate. This is an open letter to Sen. Robinson addressing these issues.

Dear Sen. Robinson,

As the debate on legalizing medical marijuana has unfolded here in Kentucky, you have invoked the Constitution’s “supremacy clause” to argue the state cannot legalize cannabis.

I appreciate your fidelity to the Constitution, but in this case, you are operating out of a fundamental misunderstanding of federal supremacy.

During a speech on the Senate floor, you read from a letter you wrote to Sen. Rand Paul stating, “According to Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution, the Constitution and federal law are superior and supersede all other state constitution, laws and regulations.”

But supremacy clause does not say this. In fact, you left the most important word of the clause out.

“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof … shall be the supreme Law of the Land”

The clause does not read, “This Constitution…and any old act Congress decides to pass…shall be the supreme law of the land.” Only acts within the scope of the federal government’s delegated powers rise to the status of supreme law. Acts outside of those powers constitute usurpation. They are, by definition, null, void and of no force.

Hamilton expressed the limited scope of federal supremacy in Federalist #33.

“If a number of political societies enter into a larger political society, the laws which the latter may enact, pursuant to the powers intrusted [sic] to it by its constitution, must necessarily be supreme over those societies and the individuals of whom they are composed….But it will not follow from this doctrine that acts of the large society which are not pursuant to its constitutional powers, but which are invasions of the residuary authorities of the smaller societies, will become the supreme law of the land. These will be merely acts of usurpation, and will deserve to be treated as such. Hence we perceive that the clause which declares the supremacy of the laws of the Union … only declares a truth, which flows immediately and necessarily from the institution of a federal government. It will not, I presume, have escaped observation, that it expressly confines this supremacy to laws made pursuant to the Constitution.”

James Iredell, a delegate to the North Carolina ratifying convention and supporter of ratification put it in even simpler terms, saying a law “not warranted by the Constitution is a bare-faced usurpation.”

St. George Tucker wrote the first extended, systematic commentary on the Constitution shortly after ratification. For nearly half a century, it was one of the primary sources for law students, lawyers, judges, and statesmen. His commentary on the supremacy clause is worth considering.

“It may seem extraordinary, that a people jealous of their liberty, and not insensible of the allurement of power, should have entrusted the federal government with such extensive authority as this article conveys: controlling not only the acts of their ordinary legislatures, but their very constitutions, also.

“The most satisfactory answer seems to be, that the powers entrusted to the federal government being all positive, enumerated, defined, and limited to particular objects; and those objects such as relate more immediately to the intercourse with foreign nations, or the relation in respect to war or peace, in which we may stand with them; there can, in these respects, be little room for collision, or interference between “the states, whose jurisdiction may be regarded as confided to their own domestic concerns, and the United States, who have no right to interfere, or exercise a power in any case not delegated to them, or absolutely necessary to the execution of some delegated power.

“That, as this control cannot possibly extend beyond those objects to which the federal government is competent, under the constitution, and under the declaration contained in the twelfth article (Tenth Amendment), so neither ought the laws, or even the constitution of any state to impede the operation of the federal government in any case within the limits of its constitutional powers. That a law limited to such objects as may be authorized by the constitution, would, under the true construction of this clause, be the supreme law of the land; but a law not limited to those objects, or not made pursuant to the constitution, would not be the supreme law of the land, but an act of usurpation, and consequently void.“

It is clear that a law not in pursuance of the Constitution is no law at all. This raises the question: does the federal government have the constitutional authority to regulate a plant within the borders of the state? The clear answer to that question is no. No enumerated power authorizes this. If you doubt this assertion, ask yourself why it required a constitutional amendment for alcohol prohibition. How is marijuana prohibition different?

Simply put, federal marijuana prohibition is unconstitutional. The states were intended to serve as a check on federal power – to ensure the general government remains within its constitutional sphere. As a state senator, you have no obligation to defer to unconstitutional federal marijuana law. In fact, James Madison said you are “duty-bound” to resist such federal overreach.

Anti-Commandeering Doctrine

But you have overlooked an even more fundamental point in this debate. Even if federal marijuana laws were constitutional, the state of Kentucky operates under no obligation to enforce them. The Supreme Court has held since 1842 that the federal government cannot compel a state to use its personnel or resources to enforce a federal law, or implement a federal program. This legal principle known as the anti-commandeering doctrine rests primarily on four SCOTUS cases with Printz v. U.S. serving as the cornerstone.

“We held in New York that Congress cannot compel the States to enact or enforce a federal regulatory program. Today we hold that Congress cannot circumvent that prohibition by conscripting the States’ officers directly. The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems, nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program. It matters not whether policy making is involved, and no case by case weighing of the burdens or benefits is necessary; such commands are fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system of dual sovereignty.”

Practically speaking, while Kentucky cannot block federal enforcement of federal marijuana laws, it is under no obligation to assist in their enforcement. The commonwealth can enact its own policies relating to marijuana and completely ignore the feds. As long as the state doesn’t actively block federal enforcement of its own law, it can enact policies contrary to federal policies. Of course, people using medical marijuana have to take the prospect of federal enforcement into consideration, but that decision rests on their shoulders.

In fact, the federal government is not enforcing federal law against medicinal cannabis users.

In 2014, Congress passed the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer amendment prohibiting the Department of Justice from spending money to prosecute medical marijuana users as long as they remain in conformity with their state laws. This remains in effect today. In short, the federal government is not prosecuting medical marijuana users in states where it is legal. In fact, they are barred from doing so.

Kentucky has every right under both the Constitution and established federal law to legalize marijuana at the state level. While I am sure your arguments relating to federal supremacy are well-intentioned, they are wrong. I hope in light of this you will reconsider your position. If you support medical marijuana, then there is no constitutional issue standing in your way. If you oppose medicinal cannabis for some other reason, simply say so. But please stop hiding behind a bastardized conception of federal supremacy.