As the coronavirus-induced economic lockdowns have tightened across the U.S., we’ve seen the emergence of a government-inspired fantasy – the myth of the nonessential business.

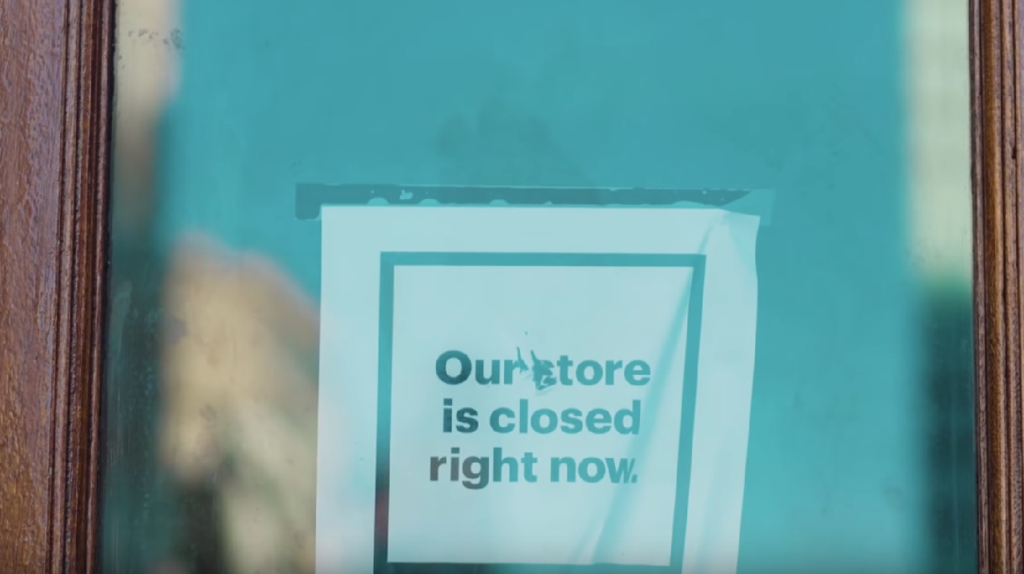

Government officials across the country have forced the closure of these so-called non-essential businesses while allowing “essential” enterprises to soldier on. Politicians and bureaucrats have developed arbitrary criteria to determine which businesses are and are not essential.

I say arbitrary because there is really no objective way to make such a determination.

In the first place, every business is essential to the owners and employees who depend on it for their livelihood. Try telling the owner of a “nonessential” craft shop that her business is non-essential when her mortgage comes due.

Here’s an important truth: the economy is life-sustaining.

Looking at the macroeconomic picture, determining what is or isn’t economically “essential” presents us with the fundamental problem of central planning: nobody possesses the knowledge necessary to grasp all of the ramifications of shutting down one business in favor of another.

The economy is an intricately intertwined system. It is diversified across time and distance. One part depends on another in a symbiotic relationship. Production and distribution form a long chain of interconnected links.

No link in a chain is “nonessential.”

When you yank one link out, however insignificant it might seem, you destroy the entire chain.

That’s exactly what these government officials are doing with their arbitrary closure of “non-essential” businesses. They are destroying the economic chain. They may take solace in the fantasy that they are only shutting down that which is nonessential, but they fail to recognize their own ignorance.

Here’s a real-life example. My friend Clay was been deemed essential during Kentucky’s coronavirus lockdown. One day at work, Clay blew out his boot. Normally, not a problem. Clay would go to the store and buy new boots. But in his infinite wisdom, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear deemed shoe stores “nonessential.” Clay wasn’t able to replace his ruined boot that he needed to do his “essential” job. Of course, he was eventually able to get boots online, but that meant several days of working with duct tape around his boot. Not to mention the fact that he really wasn’t keen on buying new work boots without trying them on. Maybe shoe stores were a little more essential than Andy thought.

Leonard Read traces the production of a simple pencil in his classic essay, “I, Pencil.” The story reveals the complexity of the economy and the power of the market by chronicling the production of a simple pencil. From the lumberjack who cuts down the tree that supplies the wood, to the trucker who drives it to the sawmill, to the oil rig worker who pumps the oil that fuels the truck, to the hundreds, if not thousands, of other people who directly or indirectly contribute to the production to the little pencil, each has a role to play and none is “non-essential.” Disrupting one of the hundreds of processes will reverberate through the system and could result in the pencil not being produced.

It’s hubris to think some group of people can micromanage an economy and determine what is or is not essential.

Of course, politicians excel at hubris.

We can debate the necessity of social distancing and economic shutdowns. Perhaps they are necessary in light of the pandemic. But we should also consider the price. Because the cost of shutting down businesses is high, both to the owner and employees who depend on them for sustenance and the broader economy that depends on them as key links in a long chain. And this is true whether governor so-and-so thinks they are “essential” or not.